Imagine staging a nine-hour production based on an ancient Hindu poem combining strains of the War of the Roses and Gotterdammerung into the cosmic grandeur of an Indian epic. Stir in a clash of two great dynasties in the hands of the gods, opposing armies locked in battle and the moral struggle of ideal heroes representing divine forces arrayed against demonic ones. All this, set against a background of primordial forests and sumptuous palaces, is encompassed in the monumental saga, “The Mahabharata” – a theatrical challenge that would intimidate most directors.

Peter Brook’s The Mahabharata provoked considerable controversy in the late 1980s. It was denounced as “only orientalism”, “cultural piracy”, or “worse, cultural rape”. It was celebrated as “the theatre spectacle of the century… a theatre event of such epic proportions that it will change the Mahabharata-as-world-text-forever” . There has been a virtual deadlock of opposing claims about Brook’s The Mahabharata and about the subsequent film adaptations of the production which were released in 1989.

However, this awesome project did not deter Peter Brook, who for 10 years persisted in putting together the complex and diverse elements contained in ”The Mahabharata,” until he finally mounted the production which received overwhelming critical acclaim this summer at the Avignon Theater Festival in France.

Before considering Brook’s The Mahabharata, we should first locate the Mahabharata in Sanskrit literature, society, and culture. The Mahabharata has been regarded as a repertory for performances and, as well, as a literary text. It was originally meant to be recited or enacted by professional bards, musicians and dancers. As a text, it is the world’s longest poem, containing, in the current Indian version, over 90,000 stanzas divided into eighteen volumes.

The central plot of the Mahabharata revolves around a conflict between two sets of cousins: the Pandavas, five brothers and their wife, married in common, Draupadi, who are aligned with dharma, and the Kurus (or Kauravas), a larger cognate group of 100 brothers and one sister, who are associated with adharma, the disruption of order and of righteousness. The leader of the Kurus sought to deprive the Pandavas of their dynastic birthright, the throne to the kingdom of Hastinapura (close to modern New Delhi). After many conflicts and a lengthy period of exile, the Pandavas were forced to battle the Kurus. While the Pandavas prevail, their victory is achieved at the price of extraordinary devastation. This relatively straightforward core narrative evolved over centuries into an elaborate exegesis on human behavior, augmented with numerous retellings of stories within stories, and manifold observations on society, culture, and religion. One of the most important works in the Hindu religious literature, the Bhagavad Gita, is included as an expository discourse on the nature of salvation given by Krishna to one of the Pandava heroes on the battlefield immediately prior to the outbreak of hostilities.

In his colossal French-language adaptation, of the ”The Mahabharata,” Brook, synthesizing all his previous theatrical inventions, did nothing less than attempt to transform Hindu myth into universalized art, accessible to any culture. This vast enterprise was undertaken by Mr. Brook with a team of close colleagues: the writer Jean-Claude Carriere, the set and costume designer Chloe Obolensky, the lighting designer Jean Kalman and a company of 21 actors from 16 countries, plus five musicians, under Toshi Tsuchitori’s direction, who play dozens of Oriental and African instruments. They all visited India – some, including Brook, several times -and closely studied Hindu scripture, costume, art and music. But the total concept – artistic and philosophical – is that of Brook.

Although parts of ”The Mahabharata” have been used in Indian dance, song and the ritual Kathakali drama, this is the first time the whole epic has been adapted for the theater. It is a compilation of the myths, legends, wars, folklore, ethics, history and theology of ancestral India, including the Hindu sacred book, the Bhagavad Ghita. Revered in India but little known in the West, ”The Mahabharata” is to South Asians what the Bible along with the Iliad and the Odyssey are to us.

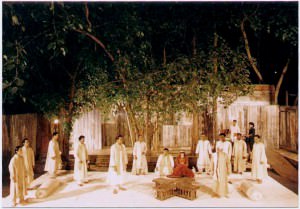

In translating this to the stage, Mr. Brook and his company make it meaningful to us through the creation of real characters and highly dramatic action rooted in Hindu culture and religion but at the same time archetypical and symbolic. There is the blind king, the ideal warrior, the devoted wife and many other mythic figures. Presented in a cycle of three plays (”The Game of Dice,” ”The Exile in the Forest” and ”The War”) over three days, or in one all-night showing, Brook’s ”Mahabharata” unfolds in an environment that in the outdoor Avignon setting combined nature with artifice. There will be a similar indoor stage set in Paris and in other cities.

Despite such efforts for respect, reverence and “dramatic truth”, Peter Brook’s “The Mahabharata” was condemned as much as it was praised, criticized primarily for not “delivering what it promises” and staying too confined in a westernized dramatic paradigm. “Brook’s Mahabharata appears as a typical work of Orientals aesthetics, and not as a representation of the unknown Orient…This is to be seen in the imposition of a Shakespearean aura and of tragic perception of fate, principally foreign to the Indian original” Brook has repeatedly defended his decisions to put the epic poem into a form more familiar for audiences of Western theatre, claiming that he was only doing what the original storytellers did by adapting the subject matter to make it relevant and recognizable to the audience, in the same way orators in one Indian region would have a slightly different way of telling the story to those in a different region. He claims the text has “a life of its own”, that “The Mahabharata itself…opened an eye and said, “This is the moment when I want to known outside India, to be really known in the West.” However, even the historian David Williams, who has written extensively on glorifying Brook’s film cannot help but find certain faults with its execution “Sadly, Brook seems unwilling to confront the dangers concomitant with applying a culturally non-specific, essentialist, and humanist aesthetic to such material. He has done himself a great disservice by never satisfactorily accounting in public for his production’s relationship with Hindu culture in India.”

Overall, Brook’s Mahabharata is a deeply humanistic retelling of the spiritual text, befitting an audience in a country as international and artistically open-minded as the UK or France. There is little sense of preaching, or even of the divine. Krishna himself, reveals many flaws – reflecting the flaws of his creation plunged into battle. I feel as though the film created by Brook/Carriere is a successful adaptation for a contemporary audience, insofar as it presents the main story and characters with grace and respect, and offers an insightful, and thoroughly modern introduction to the vastness of this ancient poem, taking its content and meaning out of India and placing it all around us.