Bertolt Brecht one of the most prominent figures in the 20th-century theatre, was poet, playwright, and theatrical reformer. He was concerned with encouraging audiences to think rather than becoming too involved in the story line and to identify with the characters. In this process he used alienation effects (A Effekts). Brecht developed a form of drama called epic theatre in which ideas or didactic lessons are very important.

Bertolt Brecht was born in February 1898 in Augsburg, Bavaria near Munich. Thanks to his mother’s influence, Brecht knew the Bible, a familiarity that would have a lifelong effect on his writing. From her, too, came the “dangerous image of the self-denying woman” that recurs in his drama. At school in Augsburg he met Caspar Neher, with whom he formed a lifelong creative partnership, Neher designing many of the sets for Brecht’s dramas and helping to forge the distinctive visual iconography of their epic theatre.

All-consuming life

In 1917, he resumed his education, this time attending Ludwig Maximilian Universitaet in Munich, where he matriculated as a medical student. He started to write Baal, a play concerned with suffering caused by excessive sexual pleasures. It sensationally depicted what were considered immoral attitudes.

Brecht’s own sex life is fascinating in many ways. He is thought to have had no fewer than three mistresses at any time throughout his adult life. He began to frequent a brothel as part of a conscientious effort to broaden his experiences. Bertold apparently pursued eight girls simultaneously, including Paula Banholzer, who gave birth to his illegitimate child.He is known to have experimented with homosexuality, often inviting literary and musically inclined male friends to on weekends to read erotic compositions. His diaries, although vague, mention his need for both males and females to fulfill his sexual desires. Brecht’s desire for experience was, throughout his life, all-consuming.

Baal, which celebrated life and sexuality, was produced in 1923. Although it did not first find any immediate producer it became eventually a huge success. At one point Brecht’s father offered to pay for the play to be printed, but only without the family name in it. Brecht’s association with Communism began in 1919, when he joined the Independent Social Democratic party. Friendship with the writer Lion Feuchtwanger was an important literary contact for the young writer. Feuchtwanger advised him on the discipline of playwriting. Brecht was named in 1920 chief adviser on play selection at the Munich Kammerspiele.

Brecht´s rise to international fame began with Trommeln in der Nacht (1922), which was awarded the Kleist Prize. Die Dreigroschenoper, after The Beggar´s Opera by John Gay, premiered at the Schiffbauerdamm Theater on August 28, 1928. It stayed in the repertoire of this theater until the Nazis seized power in 1933. Brecht made the play with the composer Kurt Weil. Gay’s work, revived by Sir Nigel Playfair at the Lyric Theatre in London, had been a great success from 1920. Brecht moved the action to Victorian times, and instead of mocking the pretentions of Italian grand opera, he attacked on bourgeois respectability. Although rehearsals were disastrous, the audience wanted to hear over and over again the duet between Macheath and the Police Chief, Tiger Brown.

After moving to Berlin in 1924, he met a communist Viennese actress, Helene Weigel, Brecht fathered his second illegitimate child, Stefan. Brecht divorced Marianne Zoff and married Helene Weigel. Helene Weigel gave birth to their second child, Barbara, but Brecht was by no means monogamous. He was obsessed with the idea of abandonment, and as a result, he abhorred ending relationships. The women in his life were important for his writing career, and modern feminist detractors often try to claim that his mistresses in fact wrote much of what was accredited to him. The allegation is largely untrue, but women such as Elisabeth Hauptmann did write significant parts of The Threepenny Opera. In addition, other mistresses included Margarete Steffin, who helped him write The Good Woman of Setzuan and Mother Courage and Her Children; Hella Wuolijoki, who allowed him to transform her comedy The Sawdust Princess into Herr Puntila and His Man Matti; and Ruth Berlau, who bore him a short-lived, third illegitimate child in 1944. Weigel was tolerant of his affairs, and she even warned other men to stay away from his mistresses because it upset him when they made their moves.

Brecht’s writings show the profound influence of many varied sources during this time and the remaining years of his life. He studied Chinese, Japanese, and Indian theatre, focused heavily on Shakespeare (adapting, among other plays, Shakespeare’s Coriolanus) and other Elizabethans, and was fascinated by Greek tragedy. He found inspiration in other German playwrights, notably Buchner and Wedekind, and he enjoyed the Bavarian folk play. Mother Courage and Her Children arguably owes much to Schiller’s Wallenstein trilogy. Brecht had a phenomenal ability to take elements from these seemingly incompatible sources, combine them, and convert them into his own works.

Fearing persecution, Brecht left Germany in February 1933, when Hitler took power. After brief spells in Prague, Zurich and Paris he and Weigel accepted an invitation from journalist and author Karin Michaëlis to move to Denmark, where they settled in a house in Svendborg on the island of Funen. This became the residence of the Brecht family for the next six years, where they often received guests including Walter Benjamin, Hanns Eisler and Ruth Berlau. During this period Brecht travelled frequently to Copenhagen, Paris, Moscow, New York and London for various projects.

When war seemed imminent in April 1939, he moved to Stockholm, Sweden, where he remained for a year. Then Hitler invaded Norway and Denmark, and Brecht was forced to leave Sweden for Helsinki in Finland, where he waited for his visa for the United States.

During the war years, Brecht became a prominent writer of the Exilliteratur. He expressed his opposition to the National Socialist and Fascist movements in his most famous plays: Life of Galileo, Mother Courage and Her Children, The Good Person of Szechwan, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, The Caucasian Chalk Circle, Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, and many others.

Brecht also wrote the screenplay for the Fritz Lang-directed film Hangmen Also Die! which was loosely based on the 1942 assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi Reich Protector of German-occupied Prague, number-two man in the SS, and a chief architect of the Holocaust, who was known as “The Hangman of Prague.” Hanns Eisler was nominated for an Academy Award for his musical score. The collaboration of three prominent refugees from Nazi Germany – Lang, Brecht and Eisler – is an example of the influence this generation of German exiles had on American culture.

“Hangmen Also Die!” was Brecht’s only script for a Hollywood film. The money he earned from writing the film enabled him to write “The Visions of Simone Machard”, “Schweik” in the Second World War and an adaptation of “Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi”.

Brecht wrote his four great plays. The Life of Galileo 1938-39, which did follow too slavishly the actual historical person, dealt with the hero’s self-condemnation for giving up his heliocentric theory in front of the Inquisition. Originally it was aimed at Broadway with Peter Lorre and Lotte Lenya playing the central roles. Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1939) was an attempt to demonstrate that greedy small entrepreneurs make devastating wars possible. “What they could do with round here is a good war. What else can you expect with peace running wild all over the place? You know what the trouble with peace is? No organization.”

Hollywood never opened its doors to Brecht, who sketched notes for more than fifty films. With one exception, he sold no stories and wrote no screenplays. For Peter Lorre, who had become a star, Brecht wrote film treatments and Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg, a stage version of Jaroslav Hasek’s The Good Soldier Švejk. He was also interested in bringing Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology to the screen. With Lion Feuchtwanger he collaborated on The Visions of Simone Machard. Brecht received at least $20,000 for his original idea. After 15 years of exile Brecht returned in 1948 to Germany. “When they accused me of wanting to steal the Empire State Building,” Brech joked, “I thought it was high time to leave.” Perhaps anticipating that Lorre’s career in Hollywood was turning down, Brecht invited his favorite actor to join his ensemble in Berlin – “I need Lorre, unconditionally,” he said. At the same time, he was well aware that Lorre was a drug addict. Brecht spend a year in Zürich working on Sophocles’ Antigone (translated by Friedrich Hölderin) and on his major theoretical work A Little Organum for the Theatre. After Zürich, Brech moved in 1949 to Berlin where he founded his own Marxist theater, the Berliner Ensemble, which was in the beginning just a group within the larger organization of the Deutches Theater. Its first production at the Stadttheater was Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti.

Brecht’s methods

Brecht experimented with Dadaism and expressionism in his early plays, but he soon developed a unique style that suited his own vision. He detested “Aristotelian” drama and the manner in which it, from his point of view, made the audience identify with the hero without enough analysis of the hero’s flaws. To him, when such drama produced feelings of terror and pity and led to an emotional catharsis, the process prevented audience members from thinking. Brecht made his dreams into realities when he took over the Berliner Ensemble. In one of his early productions, he put up signs which said “Don’t stare so romantically!”.

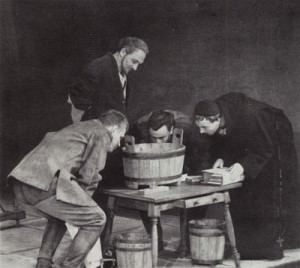

Brecht acknowledged in his work the need for the actor to undergo a process of identification with the part, and he paid tribute to Stanislavsky as the first person to produce a systematic account of the actor’s technique. Brecht required his actors to go beyond Stanislavsky and to incorporate a social attitude or judgment into their portrayal. Characterization without a critical judgment was in Brecht’s view seductive artifice; conversely, social judgment without the characterization of a rounded human being was arid dogmatism. The theatre of mixed styles and means that Meyerhold and others with the grotesque experience of modern living was transformed by Brecht into a political principle. He used mixed means and styles to expose the contradictions, inconsistencies, and dialectics of situations and characters. Brecht’s strongest theatrical effects were created through the juxtaposition of inconsistent attitudes in a character. Although the settings in Brecht’s productions were clearly theatrical, the costumes and properties were not. In Brecht’s theatre, if a chicken were to be plucked the actor did not mime or roughly approximate the action–the chicken was plucked. Costumes had to make clear the social class of the persons wearing them.

Brecht’s methods of rehearsal were especially innovative. The methods worked out in his own company, the Berliner Ensemble, established a directing collective well advanced beyond those of Reinhardt and Piscator. In Brecht’s theatre, the director, dramaturge, designer, and composer had equal authority in the production. What held the collective together and made the method workable was the story, or fable. All the elements of production were synthesized for telling this story in public. At some points the music conveyed the meaning, at other times the setting, or the actors, or the words did. Brecht often invited observers to the rehearsals in order to test the clarity of the story. The process of testing could continue into the performance period. When the company was satisfied that the staging was correct, the production was photographed and a Modellbuch was prepared with photographs set against the text to show the disposition of the stage at all times and to mark significant changes of position on the part of the actors. The Modellbuch was then available as the basis for any subsequent productions.

Brecht’s influence on the contemporary theatre has been both considerable and problematic. His Marxist views have proved a real stumbling block to his assimilation in the West, and his use of formalist techniques in the service of entertainment has presented difficulties in the socialist countries.

Brecht received the National Prize, first class, in 1951. In 1954, he won the international Lenin Peace Prize. Brecht died of a heart attack on August 14, 1956, while working on a response to Samuel Beckett’s absurdist play “Waiting for Godot”, written the year before. Even at the end, Brecht was very much interested in the modern drama of the day. He also left a will giving the proceeds of his various works to particular mistresses, including Elisabeth Hauptmann and Ruth Berlau. Unfortunately, the will lacked the necessary witness signatures and was therefore considered void. His widow, Helene Weigel, generously gave small amounts of money to the specified women. Brecht is buried in the Dorotheenfriedhof in Berlin.