“Tragedy on the stage is no longer enough for me, I shall bring it into my own life.”

Theatre should be a unsaved area, not an area for escape, but the place for realization of deepest wishes of the audience… of their fears and nightmares He tried to provoke the primitive instincts hidden beneath the civilized social veneer to describe a radical new way of performing with strong and often dark imagery… Antonin Artaud the father of theatre of cruelty, introduce his theatre as a form that would unleash unconscious responses.

He search and present the most irrational impulses stimulated by suffering and pain, danger, violence and disorientation in the audience. But, his concept of cruelty was not sadistic, because as he often said, he wanted to stimulate honest, true and cruel, and experience the dark and terrifying responses that sleeping at the hearts of performers and audience.

Artaud was a prolific writer and began writing poetry from an early age. In 1921 he began contributing to periodicals like the Surrealists’ journal Litterature and became a leading member of the Surrealist group, occasionally editing issues of leading Surrealist magazines. He wrote scenarios for a number of films, had quite a few acting credits in films like Carl Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc (1927) and acted and directed a variety of plays that included Greek and Roman classics, plays by Strindberg and works by friends like Roger Vitrac who shared his initial enthusiasm for Surrealism. After leaving the surrealist group due to disagreements with Andre Breton, he wrote a number of articles that were published between the 1920s and 1930s. These are often regarded as his most significant pieces of work and they include Art and Death (1929) and his very influential publication The Theatre and its Double (1938). In these works, Artaud forwarded ideas for the creation of a Total Theatre that he hoped would transform existing expectations of theatrical experiences.

Noting theatre’s dependency on scripts, he believed that theatre had turned into a mouthpiece for the playwright and argued that theatre practitioners should stop being bound to texts and should try to discover and articulate their own language. Artaud’s belief in a language that is unique to live performance has impacted deeply on the work of many twentieth century directors and theorists. For example, celebrated figures like Peter Brook, Jean-Louis Barrault, Jerzy Grotowski and Jacques Derrida have embraced and explored this idea in various ways and their work, in turn, has continued to inspire many other writers and practitioners.

Artaud rejected traditional views that suggested art reflected life and that theatre merely mirrored the everyday reality. Instead, he inverted this view and argued that culture often masked our real selves. For him, theatre offered a way of removing the inhibitions and restrictions introduced by social mores and cultural conditioning and uncovering what was authentic. He vehemently rejected suggestions that theatre should try and instruct spectators (see Brecht and possibly even Kosky for examples). Instead, he wanted theatre to provoke and confront spectators so that they could directly unleash what he saw as the primal, raw and real qualities in human behaviour. He argued that the aim of theatre should not be to solve social or psychological conflicts, but to express and uncover what he felt was ‘the truth.’ Perhaps because of his own experiences, Artaud regarded fear, panic and suffering as basic elements of the human condition and he wanted to stimulate these responses through the creation of what he called the Theatre of Cruelty. While he wanted to develop a theatrical approach that would violently force audiences to experience their true selves and to recognise their deepest fears, he was never able to fully realise this ambition and many of his ideas were dismissed. He did begin to explore his theories in practice in an experimental season in 1934 he called the Theatre of Cruelty and some of his ideas seem to have been applied in his adaptation of Shelley’s play The Cenci (Les Cenci 1935). Yet, as Artaud lost lucidity and became increasingly prone to hallucinations, even those working with him were less inclined to experiment with his ideas. Although he died in 1948 in relative obscurity, his work was again considered and discussed in the 1960s when he became a cult figure in France. Since then, his influence has been significant and his ideas are now often viewed as provocative and insightful perspectives on the world of theatre.

Life Full of Cruelty and Pain

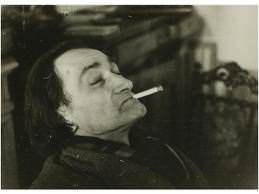

Antonin Artaud was Born in Marseille, France, on September 4, 1896, Antonin Artaud worked as an actor onstage and in film with works like La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. He was involved in the surrealist movement as a writer and came up with the idea known as “The Theater of Cruelty,” which argued that drama must abandon its emphasis on text and rely on more mysterious, primal expressions of sound, movement and light. Artaud died on March 4, 1948, in Ivry-sur-Seine, France.

His mother gave birth to nine children, but only Antonin and one sister survived infancy. When he was four years old, Artaud had a severe case of meningitis, which gave him a nervous, irritable temperament throughout his adolescence. He also suffered from neuralgia, stammering, and severe bouts of clinical depression.

Artaud’s parents arranged a long series of sanatorium stays for their temperamental son, which were both prolonged and expensive. This lasted five years, with a break of two months in June and July 1916, when Artaud was conscripted into the French Army. He was allegedly discharged due to his self-induced habit of sleepwalking. During Artaud’s “rest cures” at the sanatorium, he read Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, and Edgar Allan Poe. In May 1919, the director of the sanatorium prescribed laudanum for Artaud, precipitating a lifelong addiction to that and other opiates. He was educated at the Coll’e du Sacré Coeur in Marseilles and at 14 founded a literary magazine, which he kept going for almost four years. Still in his teens, he began to have sharp head pains, which continued throughout his life. In 1914 he was the victim of an attack of neurasthenia and was treated in a rest home; the following year he was given opium to alleviate his pain, and he became addicted within a few months.

He was inducted into the army in 1916, but was released in less than a year on grounds of both mental instability and drug addiction. In 1918 he committed himself to a clinic in Switzerland, where he remained until 1920.

On his release, he went immediately to Paris, still under medical supervision, and began to study with Charles Dullin, an actor and director. He soon began to find jobs as a stage and screen actor and as a set and costume designer. Within the next decade, he appeared on film in Fait Divers and Surcourt—le roi des corsairs (1924); Abel Gance’s Na-poléon Boneparte (1925); La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928); Tarakanowa (1929); G. W. Pabst’s Dreigroschenoper, made in Berlin (1930); and Les Croix des Bois, Faubourg Montmartre, and Femme d’une nuit (all 1930). On stage he had roles in He Who Gets Slapped (1923), Six Characters in Search of an Author (1924), and R.U.R. (1924).

At the same time, Artaud became seriously interested in the surrealist movement headed by André Breton and in 1923 published a volume of symbolist verse strongly influenced by Mallarmé, Verlaine, and Rimbaud, Tric trac du ciel (Backgammon of the Sky). Two years later, at the height of his involvement with the surrealists, he published L’Ombilic des limbes (Umbilical Limbo), a collection of letters, poems in prose, and bits of dialogue; it contained one complete work, the five-minute playlet Le Jet de sang (The Jet of Blood), which was finally produced in 1964.

Artaud broke with the organized surrealist movement in 1926, when Breton became a Communist and attempted to take his fellow-members with him into the party. Yet Artaud continued to view himself as a surrealist and in 1927 wrote the film script for La Coquille et le clergyman, perhaps the most famous surrealist film, and Les P’e-nerfs (Nerve Scales), another collection containing various literary forms.It was also in 1927 that he joined with Roger Vitrac and Robert Aron to found the Théâtre Alfred Jarry, named for the author of the 1896 play Ubu roi, which had so shocked the theatrical establishment of its time.

In 1932-1933 he published his first work of dramatic theory, Manifestes du théâtre de la cruauté (Manifestos of the Theater of Cruelty), and in 1935 staged the first work based on his theories, an adaptation of Les Cenci, heavily dependent on the earlier works on that theme by the British poet Shelley and the French novelist Stendhal. Since one of Artaud’s theories involved the breaking of the barrier between actors and audience, Les Cenci may be have been the first play ever staged in the round. In any event, it was a total failure. No understanding of Artaud would be possible without a reading of the The Theater and Its Double, translated by Mary C. Richards (1958). The best biography in English is Artaud and After by Ronald Hayman (1977). Another excellent appreciation is Artaud by Martin Esslin, and important contributions appear in The Theater of Revolt by Robert Brustein (1964) and Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag (1966). Any good history of 20th-century theatre will contain a good analysis, e.g., History of the Modern Theater by Tom Driver (1970).

In January 1948, Artaud was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. He died shortly afterwards on 4 March 1948, alone in the psychiatric clinic. It was suspected that he died from a lethal dose of the drug chloral hydrate, although it is unknown whether he was aware of its lethality. Thirty years later, French radio finally broadcast the performance of Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu.